Floating around the internet has been a rumor that each increase of 1% in the U.S. unemployment rate leads to an added 40,000 deaths — resulting from either poor physical or mental health affecting those unemployed, in some cases even after they become re-employed or retire. Renewed interest in this question was recently stimulated by a New York Post article of April 20, 2020 by John Crudele, titled: “Is unemployment really as deadly as coronavirus?”

Crudele cites as his initial source a character named Ben Rickert in the 2015 movie The Big Short about the Great Recession. Played by Brad Pitt, it’s Rickert who challenges his fellow Wall Street workers with the pronouncement: “Every 1 percent unemployment goes up, 40,000 people die. Did you know that?”

And by logical extension, the Post writer notes that increasing the unemployment rate by, say 10%, could lead to “400,000 deaths that have nothing to do with the virus and everything to do with the distressed economy.”

Apparently deciding that a quote from a movie may not be adequate substantiation, writer Crudele tracked down what may be an original source, a 1981 book titled Corporate Flight: The Causes and Consequences of Economic Dislocation written by academics Barry Bluestone, Bennett Harrison and Lawrence Baker, then again cited by Robert Carson, Wade Thomas, and Wade Hecht in their 2005 co-written book titled Economic Issues Today: Alternative Approaches, 8th Edition.

The actual paragraph of interest from the 2005 book is this: “According to one study [the one by Bluestone et al.], a 1 percent increase in the unemployment rate will be associated with 37,000 deaths (including 20,000 heart attacks), 920 suicides, 650 homicides, 4,000 state mental hospital admissions and 3,300 state prison admissions.”

While the specific impetus of the 1981 research was about a different cause of unemployment — then the concern was corporate flight from America, today it’s pandemic — this early study asks a question that has never been more pressing than today. That question is: Does unemployment affect mortality?

The New York Post writer’s story should not be viewed as an endorsement of this prior research. The author cites two differences between then and now. One is that, in the current situation, the federal government has “acted quickly to help the unemployed” which did not happen in earlier years when companies were moving overseas. Another factor cited is that much of the current job loss is for furloughed workers who may “get their jobs back once companies reopen their doors.”

The concluding remark of the Post article is: “Let’s hope that the data from 1981 is — excuse the expression — dead wrong.” But, really?

Should we discount the relevance of this historical precedent. The potential size of the impact cited by Bluestone, et al is particularly troublesome. Could just a 1% point increase really be associated with 37,000+/- U.S. deaths? So again, this got me asking: Could this earlier research really be valid — potentially applicable even today?

And that’s what led to the bit of statistical research I have conducted which essentially concludes: Yes, there appears to be a definite association of mortality with unemployment.

And the impact likely is now greater than estimated by Bluestone, Harrison, and Baker nearly 40 years ago. With this updated analysis, a more current estimate appears to be more in the range of 47,500 deaths for every 1% point increase in America’s average annual unemployment rate.

The rest of this blog article describes how this tentative conclusion is reached.

THE SCIENCE OF UNEMPLOYMENT-MORTALITY RESEARCH

Before launching into my own statistical examination, I decided to first check out whether and in what ways other similar research has been conducted more recently. While not widely known or publicized, there actually is a compendium of academic research assessing the relationship of unemployment to various indicators and causes of mortality.

A public health and epidemiology researcher, named M. Harvey Brenner, PhD, has conducted numerous studies focused on the relationship between economic well-being and community health. Dr. Brenner has held positions in public health and epidemiology at institutions including the University of North Texas Health Science Center, Hanover Medical University, Johns Hopkins University and Yale University.

In a BBC podcast/interview dated March 4, 2016, Dr. Brenner is quoted as stating that the figure of 40,000 U.S. deaths for every 1% rise in unemployment is still a “good rule of thumb.” This statement is based on his work dating back to the 1970s. In a 1979 hearing before the Joint Economic Committee of the U.S. Congress, Dr. Brenner noted that a 1% increase in unemployment is related to a 2% increase in total U.S. mortality. Added mortality follows behind increased unemployment over a 2-5 year time lag. And with more recent work, Dr. Brenner has pressed forward with continued detailed analyses— encompassing research on both sides of the Atlantic.

For example, a May 2016 study by Dr. Brenner titled The Impact of Unemployment on Heart Disease and Stroke Mortality in European Union Countries was prepared under the auspices of the European Commission. While focused on two indicators of unemployment-related mortality, the research begins by summarizing a range of European and U.S. epidemiological studies that “have shown since the 1970s that socioeconomic status (SES) is a stable risk factor for illness and mortality in individual persons.” A key observation from this literature review is that: “Unemployment is an important risk factor for mortality and morbidity — especially if the unemployment is of long duration.”

An underlying factor behind employment-related mortality is the stress resulting from unemployment. This stress manifests itself psychologically in outcomes that have been cited to range from depression to human violence including indicators as for suicide and homicide. Economic stressors include loss of income, poverty and economic inequality. Medical implications range from changes in diet and exercise to mortality as with heart disease and stroke.

Specific findings of Dr. Brenner’s empirical research from the European experience of 2000 - 2010/11 (including the period of the Great Recession) include the following:

The incidence of both heart attacks and strokes in the EU is strongly correlated with increases in unemployment.

There appears to be some delay between the time of becoming jobless to when an individual is at greatest risk of death — about a two-year lag for heart-related mortality and a somewhat longer delay averaging about three years for strokes.

Southern European countries appear to experience less incidence of unemployment related mortality than northern Europe — for reasons not entirely clear but potentially linked to healthier Mediterranean diets, warmer winters and more closely knit family ties, offering greater “social cohesion” for southern countries.

Older workers experience higher rates of unemployment related mortality — including “spread effects” that influence health beyond a person’s normal working life and extending across to other members of affected families.

This background review provided a starting point for thinking about how to frame an updated initial statistical analysis, assessing the historical relationship between unemployment and mortality in the U.S. — a discussion which now follows.

A MORTALITY-UNEMPLOYMENT HYPOTHESIS

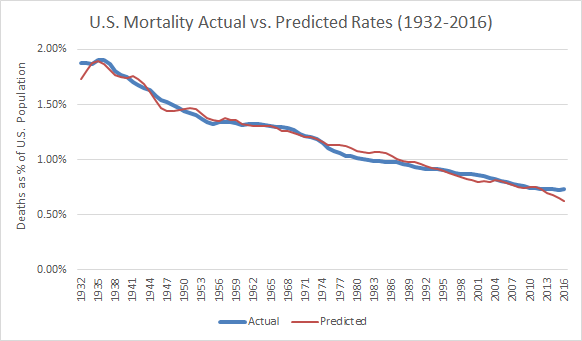

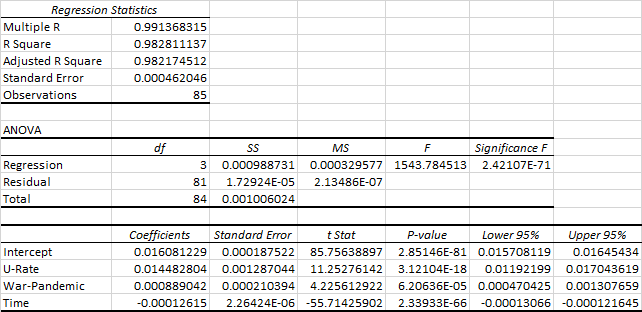

For this initial research, I have applied a simple linear regression model to assess the statistical relationship between unemployment and mortality rates in the U.S. — over a time period extending from 1929 (just at the onset of the Great Depression) to 2017, the years for which data was most readily available from recognized sources. Four data variables are assessed with this statistical testing process:

Age adjusted mortality rates (as a % of the population), available for the years 1900-2017 as reported by the National Center for Health Statistics of the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Note: CDC/NCHS data adjusts death rates after 1998 to the age composition of the U.S. population as of 2000. Death rates prior to this time are taken from historical data.

Annual average civilian unemployment rates as reported by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics and reported by the Economic Report of the President (2020), covering the years from 1929-2019.

Years with significant (above normal) mortality due to non-employment factors but that address considerations such as wars or pandemics are also included as a third binary variable in the analysis (as will be further described below).

Time trend is of particular importance for mortality as rates have experienced a strong downward trend over the last century with the advent and continued positive health results of modern medicine.

The form of the mathematical relationship being tested is:

Mortality Rate = f (Unemployment Rate, War/Pandemic, Time)

But before we get to the statistical testing, let’s take a look at the underlying data.

U.S. UNEMPLOYMENT & MORTALITY EXPERIENCE

We start the presentation of U.S. unemployment and mortality experience since 1929 with the first in a series of graphs. The red line shows annual deaths in the U.S. as a percentage of total (age-adjusted) U.S. population. The blue bars depict annual average unemployment rates for the same years. Trend lines are also shown for mortality and unemployment (together with the statistical regression equations and statistical fits measured as R-squared).