One year ago, I evaluated the changing face of U.S. housing demand — looking a decade ahead. A key finding was that aging baby boomers age 75-84 can be expected to represent the #1 source of net housing demand across the U.S. through to 2029. That year ago blog is available by clicking on this link for:

The Changing Face of U.S. Housing Demand.

This current post carries that analysis one step further — addressing the question: What then will be the changing face of housing demand two decades ahead? The story-line for the next two decades might best be summed up as housing famine, then feast.

Three preliminary conclusions emerge from considering U.S. housing needs not just over the 2020s, but into the 2030s:

The housing market will be whipsawed by the aging and then dying baby boom generation over these two decades — with extraordinary demand in the 2020s followed by a potentially glutted market in the 2030s.

Addressing the rapidly changing dynamics of baby boomers will help to smooth market function for other age cohorts — especially the large millennial cohort who today are scrambling for affordable and increasingly family-friendly housing.

Finally, shifting to a mix of more rental and less ownership product can facilitate more efficient market response than likely will otherwise be possible.

Review of 2019-29 Forecast

As noted, the #1 finding of the earlier analysis covering our current decade is that aging baby boomers age 75-84 represent the single largest source of net household growth from 2019-29. As illustrated by the following graph, this older boomer cohort age is followed by younger boomers age 65-74 as the 2nd largest source of housing demand (by age of householder).

Note: This forecast assumes in-migration to the U.S. represents a 3.4% increase in population each decade. A similar assumption is applied to the 2029-39 projection below.

Taken together, those age 65-84 can be expected to account for an estimated 94% of the net change in housing demand — for an added 9.7 million households nationwide — over this current decade. Millennials age 35-44 represent 26% of added household demand. Other working age adult cohorts of those under 34 and those 45-64 represent flat or declining shares of U.S. housing demand.

So, What About Two Decades From Now?

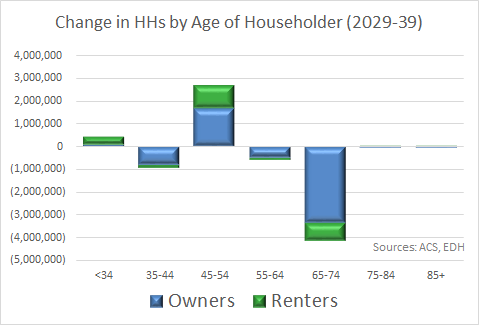

From 2029-39, the U.S. housing market takes another abrupt turn — as illustrated by the following graph.

Three key findings are of note:

Over a 2-decade horizon, all household age cohorts (except those millennials who are by then age 45-54 and a small number of those under 34) will represent declining household demand. Baby boomers who all will be passing through their 70s and 80s will no longer represent a source of household growth as those who graduate into this age cohort will be offset by generally older counterparts facing mortality. Retirees age 65-74 will represent the largest reduction in net housing demand as the previously large cohort of aging baby boomers is offset by a much smaller population of maturing Gen X householders.

Total housing demand will shrink from a need for an estimated 9.7 net new housing units in the current decade to a net reduction of 2.6 housing units in the following decade of 2029-39. If this scenario plays out consistent with current demographic trends, the nation’s current housing shortage will be replaced by housing surplus.

Finally, as visually depicted below, the housing surplus that emerges from 2029-39 can be expected to be greatest for owner-occupied units — while rental demand two decades out remains essentially flat.

Implications

Detailed discussion was provided by my prior blog post of implications of the 2019-29 housing demand shift now underway. What are we to make of the initial outlines of what might emerge in the following decade of 2029-39? And how are these two decades to be addressed in their totality?

First and foremost, it is clear that the U.S. housing market will be whipsawed by the aging and then dying baby boom generation (those born from 1946-64) over these two decades. Potentially exacerbated by renewed inflation and increased interest rates, it appears increasingly challenging to keep up with extraordinary housing demand now being experienced through the 2020s — only to be followed by market glut in the 2030s. Making these market transitions less abrupt and financially wasteful should be an objective of both private industry participants and public sector policy initiatives appropriate now and in the years ahead.

Second, addressing the unusual dynamics of the now intense followed by fading baby boom dynamic will help to smooth market functionality for other age cohorts — especially the also large grouping of millennials who today are scrambling for affordable and increasingly family-friendly housing. The sooner that boomers can be enticed out of large single family home-ownership product into other existing right-sized and/or new innovative senior housing offerings, the easier it will be to serve other market demographics with less risk of long-term single-family residential overbuilding.

Third and finally, while home ownership likely will remain an important part of the American dream for generations to come, shifting to a mix of more rental and less ownership product can serve to facilitate more efficient market response than would be otherwise possible. Rental housing fits more with an ever more urban demographic profile of the American housing and can more rapidly be built, adapted from other uses and/or removed from the housing inventory in response to changing market conditions than single-family ownership product.

For comments on this blog post or to request inclusion on my email notification list for future E. D. Hovee blog posts, please email me, addressed to: ehovee@edhovee.com

Also note: A listing of and links to past blog posts is available at:

Blog Post Listing.